SZYMON PUSTELNY

Scientist, entrepreneur, husband, and father

ZERO- AND ULTRALOW FIELD

NUCLEAR MAGNETIC RESONANCE

Zero- and Ultra-Low-Field (ZULF) Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) is a novel spectroscopic technique that allows for investigations of spin dynamics under the unique NMR condition of no magnetic field. This emerging modality opens a new window into the very heart of

molecular structure, where the subtle interactions between nuclear spins, known as J-couplings, take center stage, revealing exquisitely detailed chemical and structural information.

INTRODUCTION

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is a non-destructive analytical method that determines molecular structure, dynamics, and interactions by monitoring the atomic nuclei evolution in a strong magnetic field. The NMR signals (oscillating magnetic fields) are mathematically converted into spectra that report on chemical environment, connectivity and motion. From small organic molecules to proteins, batteries and porous materials, NMR has become an essential tool across chemistry, biology, medicine and materials science, and provides the physical basis for clinical magnetic resonance imaging.

STRONG MAGNETIC FIELD IN NMR

For several decades, progress in NMR spectroscopy has depended on the availability of ever-stronger magnets. This is associated with two factors. First, a static magnetic field removes the degeneracy of nuclear-spin energy levels. As field strength increases, the energy separation grows, producing a proportionally larger population difference between the levels at thermal equilibrium. The resulting increase in bulk magnetisation directly raises the amplitude of the NMR signal. Second, the field determines the precession frequency of the spins. Higher frequencies generate larger voltages in the detection coil operating based on electromagnetic induction. In turn, the signal-to-noise ratio is increased. These two factors continue to drive efforts to construct higher-field NMR spectrometers.

DIAMAGNETIC SHIELDING AND CHEMICAL SHIFT

In NMR spectroscopy, the resonance frequency of an isolated nucleus is affected by the electron cloud surrounding it. Circulating electrons generate a small local magnetic field that usually counteracts, and less often reinforces, the applied field, displacing the resonance from a defined reference; this displacement is the chemical shift. Expressing shifts in parts per million removes explicit dependence on magnet strength, so spectra from 200 to 1,200 MHz can be compared directly. In absolute hertz, however, the same ppm separation increases with field strength, giving high-field magnets superior chemical resolution. Because shielding responds to hybridisation, electronegativity, hydrogen bonding, ring currents and conformational changes, chemical shifts offer a detailed, first-line map of molecular structure.

CHALLENGES OF HIGH-FIELD NMR

While extremely powerful, the strong magnetic fields of conventional NMR present significant challenges. For one, generating such fields requires superconducting magnets maintained at cryogenic temperatures, which makes NMR spectrometers and MRI scanners bulky, costly, and maintenance-intensive. Moreover, the intense field poses safety risks: ferromagnetic objects can be violently attracted and become dangerous projectiles, and medical implants may malfunction. Uniformity of the field across the sample is also critical, as any slight inhomogeneity degrades spectral or spatial resolution. For decades, these technical, economic, and safety constraints have driven interest in interesting, yet quite exotic low-field NMR.

NMR AT ULTRALOW OR EVEN TRULY ZERO FIELDS

The technical, economic and safety constraints of strong magnets have inspired a very different strategy in NMR, i.e., performing NMR in much weaker, or even truly zero, magnetic fields. However, the instant the field is weakened, the benefits that underpin conventional NMR vanish, and a new array of obstacles rapidly takes their place. In milli-, micro- or even nanotesla fields the thermal population difference between nuclear‐spin states is negligible, so the native NMR signal becomes vanishingly small. Because at the fields nuclei now precess at only (kilo)hertz, As a result, Faraday coils generate scarcely any voltage, and the efficiency of conventional inductive detection collapses. Finally, the chemical shift that anchors high-field spectroscopy is no longer observable, making traditional analytical protocols impossible. Only through the development of novel techniques and methodologies can NMR signals be detected and exploited in the zero- and ultra-low-field (ZULF) regime.

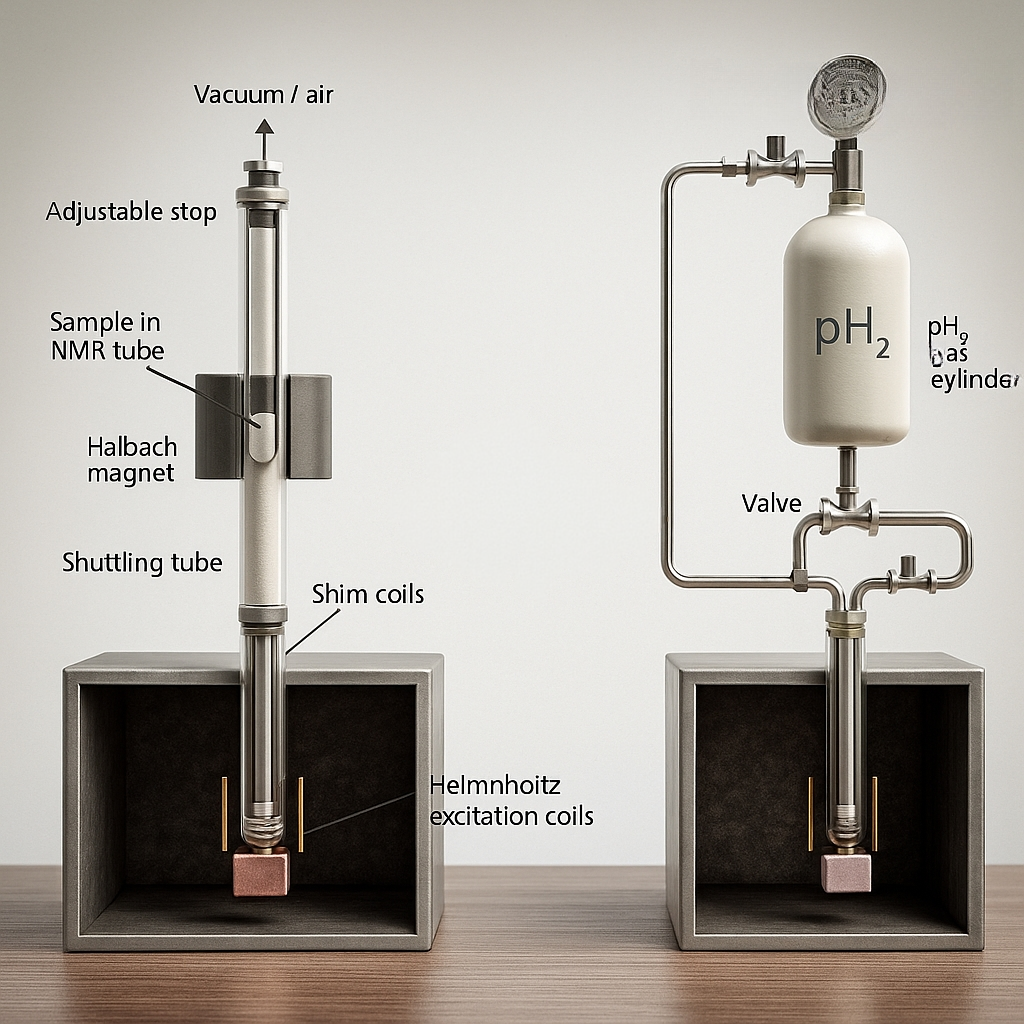

POLARIZATION

The first challenge is the very low spin polarization at ZULFs, which

can be addressed by two complementary strategies. The first is remote

prepolarization of the sample in a strong magnetic field, followed by

shuttling the sample into the ZULF region for detection. Because the polarization field does not need to be extremely homogeneous,

inexpensive and compact permanent magnets, capable of generating fields up to approximately 2 T, can be used. The second strategy is hyperpolarization: a family of techniques that exploit specific physical processes to enhance nuclear spin polarization by orders of magnitude beyond the thermal limit. Importantly, several of these methods can enhance nulcear-spin polarization directly in zero- or ultra-low-field environments, making them ideally suited for ZULF NMR. These approaches allow us to circumvent the need for bulky and expensive superconducting magnets.

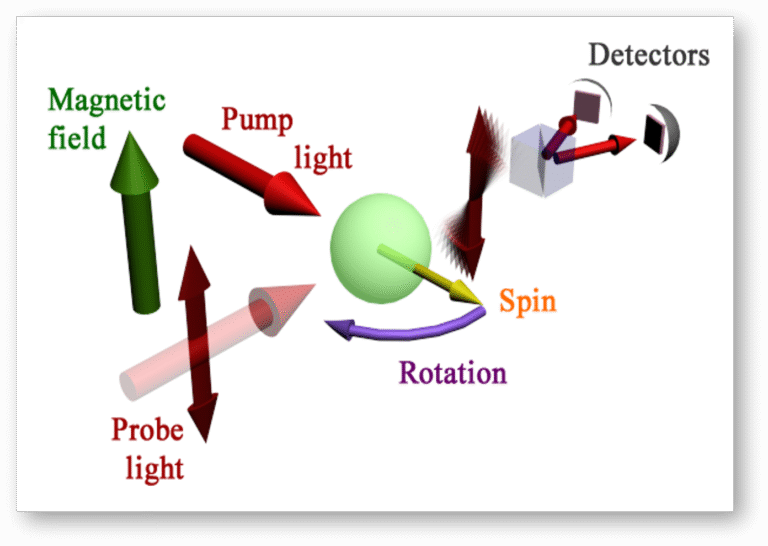

OPTICAL DETECTION OF NMR SIGNALS

Since induction detectors work by sensing changes in magnetic flux, their performance in weak fields corresponds to detecting signals at very low frequencies (< 1 kHz), rendering traditional pick-up coil magnetometers ineffective. To overcome this limitation we employ atomic magnetometers, which deliver the highest available sensitivity from DC up to about 1 MHz magnetic fields while remaining inexpensive and easy to operate. Their superior performance is especially valuable in ZULF NMR, where nuclear spin precession occurs only in the hertz-to-kilohertz range.

J-COUPLING SPECTROSCOPY

In a zero magnetic field, the chemical shift, which is the foundation of the analytical capabilities of NMR, disappears. Simultaneously, in molecules containing different types of nuclei, the dominant interaction under these conditions is the scalar coupling, also known as J-coupling. This indirect interaction between nuclei, mediated by electrons, not only provides fundamental information about the molecule’s structure but also about the dynamics of intramolecular interactions.

J-coupling spectroscopy provides valuable insights into the geometry of the molecule, including bond angles and dihedral angles. It is a weak interaction, with coupling constants typically ranging from a few hertz up to about 200 Hz can be used to monitor the progress of chemical reactions and analyze their kinetics. Free from various limitations (e.g., due to magnetic-field inhomogeneity), the ultranarrow (as narrow as 10 mHz), the technique arms the users with the unique analytical capabilities.

OUR WORK

For over ten years our group is involved in research on ZULF NMR. Our interests focuses on several different subjects:

- Chemical Safety & Fingerprinting

- Biomolecules & Biofluids

- Hyperpolarization for Trace Detection

- Quantum State Engineering & Tomography (Emerging)

- Portable ZULF NMR Platforms

CHEMICAL FINGERPRINTING & SAFETY

ZULF J-spectroscopy captures zero-field J-spectra that act as molecular barcodes, immune to distortions at high field and capable of identifying compounds even in opaque samples or through metal.

We applied this to a broad set of chemicals, detecting both major features and subtle differences. In particular, we identified hazardous organophosphorus compounds such as trimethyl phosphate and dichlorvos from a single spectrum, with high resolution, minimal false positives, and sensitivity to trace amounts.

This combination of specificity, low-level detection, and operation in challenging environments makes zero-field chemical fingerprinting a powerful tool for safety, security, and industrial monitoring.

BIOMOLECULES AND BIOFLUIDS

Modern diagnostics face challenges in detecting specific molecules in complex biofluids. High-field NMR often produces crowded spectra that obscure signals. We overcome this using ZULF NMR, and detect such metabolites as urea even in water-rich samples. This approach leverages near-zero magnetic fields to generate clear molecular “barcodes,” simplifying analysis and revealing information that is otherwise hidden.

Field-dependent relaxometry further probes the molecular environment, detecting subtle changes such as oxygen variations in blood via hemoglobin’s magnetic signature. This paves the way for non-invasive monitoring of blood oxygenation.

Combining these methods allows rapid analysis of relaxation properties in whole blood, identifying new biomarkers for conditions like inflammation. Our goal is portable, non-invasive diagnostics that deliver fast, accurate results at the point of care

HYPERPOLARIZATION FOR TRACE DETECTION

To overcome the fundamental challenge of sensitivity in trace analysis, we integrate ZULF NMR with a powerful hyperpolarization technique known as SABRE (Signal Amplification By Reversible Exchange). This method utilizes parahydrogen to dramatically enhance the NMR signal of a target molecule, boosting its visibility by several orders of magnitude and enabling detection at previously inaccessible low concentration.

Our work successfully merges the exquisite selectivity of ZULF spectroscopy with the massive signal boost from SABRE. By applying this combined approach, we have demonstrated the ability to detect and identify molecules, such as pyridine and its derivatives, at ultra-low, micromolar concentrations. The hyperpolarization process is rapid, allowing for high-contrast detection in a matter of seconds. This transforms ZULF NMR from a powerful identification tool into a highly sensitive instrument capable of finding a needle in a haystack.

This leap forward represents a paradigm shift for analytical chemistry and molecular sensing. The ability to achieve both high specificity and extreme sensitivity opens the door for applications that were previously out of reach. This includes the potential for early-stage medical diagnostics by detecting trace biomarkers, real-time environmental monitoring for pollutants, and enhanced security screening for hazardous chemical agents.

Selected publications

Selected articles:.

- A. Barskiy, J. W. Blanchard, D. Budker, J. Eills, S. Pustelny, K. F. Sheberstov, M. C. D. Tayler, and A. H. Trabesinger, Zero- to ultralow-field nuclear magnetic resonance, Prog. Nucl. Magnet. Reson. Spect. 148-149, 101558 (2025) – Full text

- Alcicek, P. Put, A. Kubrak, D. Barskiy, S. Gloeggler, J. Dybas, and S. Pustelny, Zero- to low-field relaxometry of chemical and biological fluids, Comm. Chem. 6, 165 (2023) – Full text

- P. Put, S. Alcicek, O. Bondar, Ł. Bodek, S. Duckett, and S. Pustelny, Detection of pyridine derivatives by SABRE hyperpolarization at zero field, Comm. Chem. 6, 113 (2023) – Full text

- S. Alcicek, E. van Dyke, J. Xu, S. Pustelny, and D. A. Barskiy, 13C and 15N Benchtop NMR Detection of Metabolites via Relayed Hyperpolarization, Chem.-Meth. e202200075 (2023). – Full text